Intersectionality

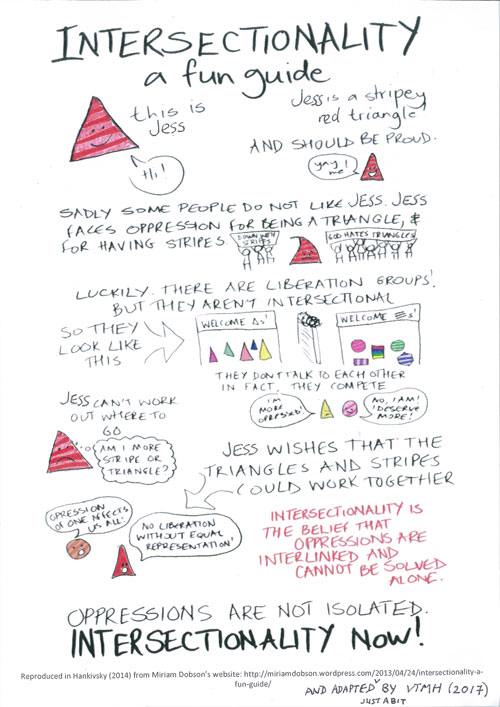

Human lives cannot be explained by single categories, such as gender, race and sexual orientation. The intersection of these categories can produce both experiences of privilege and oppression. Intersectionality addresses discrimination that arises at the specific intersection of multiple identities.

KEY POINTS

- Part of taking an intersectional approach is recognising people’s lives are multi-dimensional and complex; we expect multiple stories

- Human lives cannot be explained by single categories, such as gender, race, sexual orientation etc. Lived experience is an interactive process that goes beyond individual labels

- Lived experience is shaped by the interaction of identities, contexts and social dynamics

- People can experience privilege and oppression simultaneously

- Structural inequity interacts with contextual factors and social dynamics, increasing marginalisation, inequity, and health disparity

- To understand someone’s experience, we must also understand structures and systems

- Relationships involve power dynamics and power imbalances are inevitable. The question is how we acknowledge and negotiate power, particularly in institutions

- Reflexivity can support service providers to increase their awareness of their positions of power

- Urges transformation and collective work towards social justice

Be open to addressing the issues

Listen in order to understand

Develop a diversity responsiveness plan

Become a reflective, learning system

Intersectionality is an analytic framework that addresses identify how interlocking systems of power impact those who are most marginalized in society. Taking an intersectional approach means looking beyond a person’s individual identities and focusing on the points of intersection that their multiple identities create. The term was coined by black feminist and legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw to describe how individuals with multiple marginalized identities can experience multiple and unique forms of discrimination that cannot be conceptualised separately1.

[Black women] sometimes experience discrimination in ways similar to white women’s experiences; sometimes they share very similar experiences with Black men. Yet often they experience double discrimination–the combined effects of practices which discriminate on the basis of race, and on the basis of sex. And sometimes, they experience discrimination as Black women–not the sum of race and sex discrimination, but as Black women (p. 149).

Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;139:139–167.

Crenshaw advocated that discrete definitions of discrimination as occurring within a single category (e.g. attributing discrimination to either race or gender but not both) did not capture the experiences of people who experience discrimination due to the specific intersection of their multiple identities1. Focusing on the experiences of black women and other women of

When feminism does not explicitly oppose racism, and when antiracism does not incorporate opposition to patriarchy, race and gender politics often end up being antagonistic to each other and both interests lose.

Intersectionality has been a widely applied framework in studying and addressing issues of discrimination ranging from gender, race, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other identities. Intersectionality has also been applied within the context of reducing health disparities amongst socially disadvantaged groups

An intersectional lens to equity requires us to engage in a reflective process,

When used thoughtfully, intersectionality

I would like to see the next generations of QTIPOC who are able to retain their cultural identities as well as their sexual or gender identities. I see too many times young people of colour remove themselves from their culture, and I was there too… If I could go back, I would tell my teenage self not to lose that part of myself, and that it would only get harder for myself by denying an essential part of my identity.

AN ETHICAL STANCE

- Centering Ethics helps us put our shared ethics at the centre by taking positions against neutrality and for justice.

- Doing Solidarity means that we see all of our work towards justice as inter-connected and that we act collectively.

- Naming Power requires identifying injustices and taking positions that address abuses of power. It includes witnessing peoples’ resistance to oppression, addressing privilege, and creating practices of accountability.

- Fostering Collective Sustainability acknowledges that we are meant to do this work together. We resist individualism and invite collective social responsibility for a just society without putting the burden of an unjust society on the backs of individual workers.

- Critically Engaging with Language acknowledges the power of language and commitments to using language in liberatory ways. It welcomes the language that occurs outside of words.

- Structuring Safety creates practices that invite safety into our work, informs us to act as allies where we are privileged and to honour collaboration.

DOING JUSTICE AS A PATH TO SUSTAINABILITY IN COMMUNITY WORK

Vikki Reynolds 2010

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- How do your own race, gender, class, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other identities intersect to form your experiences? Do you experience any forms of inequity or discrimination due to your identities? Are some more privileged? Are some less so?

- What power dynamics do you experience in your occupation, family life, and other social contexts? Are there times in which you hold more power due to the nature of the relationship (e.g. between a doctor and their patient) or vice versa? In what ways do these power dynamics affect your interactions with other people and services?

- What are some ways in which you can support people to share the complexity of their lives?

RELATED VIDEOS

Identity is not a self-contained unit

Intersectionality is a prism for understanding certain kinds of problems…how the convergence of racial stereotypes and gender stereotypes may play out. You can’t change outcomes without knowing how they have come about.

What is intersectionality?

BroadAgenda 50/50 by 2030 Foundation, Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis (IGPA), University of Canberra, Australia.

REFERENCES

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139-167.

- Crenshaw, K. (1993). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of colour. In Critical race theory: the key writings that formed the movement, K. Crenshaw, N. Gotanda, G. Peller, & K. Thomas (eds.). New York: New Press, 357-383.

- Lopez, N., & Gadsden, V. J. (2016). Health inequities, social determinants, and intersectionality. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washing, DC.

doi : 10.31478/201612a - McNair, R. (2012). A guide to sensitive care for lesbian, gay, and bisexual people attending general practice. The University of Melbourne: Melbourne.

- Meijia-Canales, D., & Leonard, W. (2016). Something for them: meeting the support needs of

same sex attracted and sex and gender diverse (SSAGD ) young people who are recently arrived, refugees, or asylum seekers. Monograph series no. 107. GLHV@ARCHS, La Trobe University, Melbourne. - Noto, O., Leonard, W., & Mitchell, A. (2014). Nothing for them: understanding the support needs of LGBT young people from refugee and recently arrived backgrounds. Monograph series no. 94. Melbourne, Australia: The Australian Research Centre in Sex Health and Society, La Trobe University.

- Olena Hankivsky, Intersectionality 101, The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU April 2014, accessed 3 December 2018

- J. Chen (2017) Intersectionality Matters: A guide to engaging immigrant and refugee communities in Australia. Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health. Melbourne