Culture

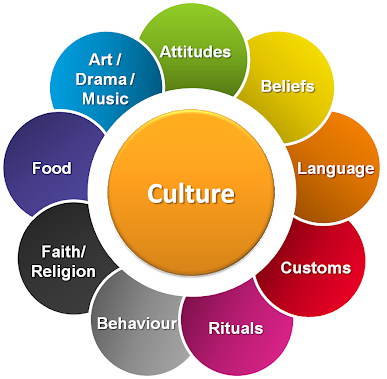

Culture is a learnt and dynamic process that influences how we experience the world. It can be recognised in external ways such as language, food and rituals, and in more internal ways such as values, emotions, and beliefs.

KEY POINTS

- Everyone has a culture.

- Culture is individual. Individual assessments are necessary to identify relevant cultural factors within the context of each situation for each person.

- An individual’s culture is influenced by many factors, such as race, gender, religion, ethnicity, socio-economic status, sexual orientation and life experience. The extent to which particular factors influence a person will vary.

- Culture is dynamic. It changes and evolves over time just as individuals change over time.

- Reactions to cultural differences are automatic, often subconscious, and influence the dynamics of the health professional-client relationship.

- A health professional is influenced by personal beliefs as well as by professional values.

- The health professional and community worker is responsible for assessing and responding appropriately to the client’s cultural expectations and needs.

- There is as much difference within cultures as there are between cultures.

Listen and ask the specific needs of the individual rather than making cultural assumptions.

What is Culture

We understand the world through the lens of culture.

Culture is a learned and dynamic process that influences how we experience the world1. Culture can be identified externally through things such as language, food, and traditions, and also in more subtle ways, internally influencing people’s values,

We all have Culture

Every individual has a culture which is influenced by a range of factors, such as their gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and socio-economic status. The impact of culture varies within and across individuals and groups, and people often adjust their

Culture is Broader than Ethnicity

Culture is broader than ethnicity or language groups. Traditionally, cultural diversity was understood as an approach to meet the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) individuals and communities, inclusive of ethnicities and language groups and later faith identities. More recently the language of ‘diversity’ has been used to

Families and communities often have their own internal cultures. When at work or engaged in community activities we are part of

The Danger of a Single Story

We all ‘carry’ our culture; every encounter is a cross-cultural encounter.

Sometimes people use stereotypes to understand each other, however connecting via cultural stereotypes is problematic as they can create misunderstandings about values and beliefs, exclude identities and make experiences invisible. All cultures have micro cultures and descriptions about cultures are unlikely to be applicable to every individual within that culture.

The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story… I’ve always felt that it is impossible to engage properly with a place or a person without engaging with all of the stories of that place and that person. The consequence of the single story is this: It robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar.

Seeing Culture

Cultural responsiveness describes the capacity to see, understand, and respond to the needs of diverse communities. The approach was initially developed to increase access to health care by culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities3 and highlights the benefit of understanding that all individuals exist within a cultural context. In this way, a culturally responsive approach supports people to ‘see each other’ and their uniqueness within their cultural context, whilst working together to find ‘common ground’.

Seeing culture requires people to examine assumptions about how we make meaning in the world.

Safe and Inclusive Practice

Cultural safety involves acknowledging how power operates in service systems and in consumer-practitioner relationships. To either support or create barriers in accessing support. Practicing cultural humility is vital to fostering culturally safety, as we take steps to critically reflect on our biases and beliefs to avoid imposing our own cultural values on others.

This requires practitioners to recognise that they can never fully understand another person’s experience.5 It also asks us to develop partnerships with, and learn from others,1 to actively respond to power imbalances, and to commit to critical self and systems level reflections.

Cultural Humility

- Expect diversity; adopt diversity informed practice as your usual approach

- Expect complexity, culture is constantly changing and humans are complex

- Recognise the relationship between cultural identity, (in)visibility and power

- Seek connection with people in their experiences of invisibility; meet them where they are at

- Engage with and hold multiple perspectives and stories

- Reflect on the relationship between power and privilege

- Ask questions and seek to understand someone’s experience of the world

- Understand that nobody is an expert in anyone else’s experience

- Recognise the importance of, and take action to, share power

- Collaborate to co-constructing solutions together

- Negotiate shared understandings; seek ‘common ground’

- Ask for, and respond to feedback; create safe systems for two way learning

- Engaging in an ongoing process of self and systems level reflection

[I would like service providers and community leaders to understand] the constant conflict within ourselves and our cultural beliefs. That we cannot abandon all of these, so it doesn’t work to keep telling us to be ourselves. We value a collectivistic kind of society where everyone is in harmony.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- How would you describe your culture? What parts of it do you most identify with?

- How does your culture influence the way you think and act in the world?

- What part of your cultural identity is most helpful to you/what part is unhelpful?

- If stereotypes are incomplete, what can help us to understand each other better?

- What do you currently do to find common ground in your relationships and interactions?

- What can you do today to be more culturally safe and responsive?

RELATED VIDEO

Taiye Selasi: Don’t ask me where I’m from, ask me where I’m local.

When someone asks you where you’re from … do you sometimes not know how to answer? Writer Taiye Selasi speaks on behalf of “multi-local” people, who feel at home in the town where they grew up, the city they live now and maybe another place or two.

REFERENCES

- Victorian Transcultural Mental Health, 2015. Orientation to Cultural Responsiveness: Online Resource.

- Kirmayer, J. (2012). Rethinking cultural competence. Transcultural Psychiatry, 49(2). 149-164.

- Mental Health in Multicultural Australia (2014). Key concept 1: Cultural Responsiveness.

- Victorian Transcultural Mental Health, 2018. Cultural Diversity and Assessment: Online Resource.

- Waters, A., & Asbill, L. (2013). Reflections on cultural humility. CYF News, American Psychological Association.

- Best Practice Guide: Common Threads, Common Practice. Working with immigrant and refugee women in sexual and reproductive health. Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health 2013. P12.

- College of Nurses of Ontario: Practice Guidelines, Culturally Sensitive Care, 2009